Hello, everyone! I hope you’re all doing well and enjoying summer~ I’m certainly having a time and a half because as soon as it became summer, my home decided that it was going to go from wet and cold to blazing hot, and now I’m afraid it’ll be as intense a heat wave as last year… Such high temperatures really aren’t natural in my part of the world, but what can you do when it’s global warming…

And ah, I’m shaking my fist at the fact that this blog entry is once again late ahaha. Unfortunately last week, while I did arrive home while it was still the weekend, I had just been on a giant road trip and I was way too tired to do much else besides sleep. It is fun though because I attended my younger brother’s convocation (his graduation ceremony), and I’ll be off to attend my own in just a few weeks! It’s pretty funny how he’s younger than me, yet he gets to have his first, since mine was delayed by COVID. Also, almost forgot to mention, but my brother’s convocation was actually on my birthday this year! Kind of amusing since when he graduated from high school, it was also basically on my birthday. 😆

Anyway, that’s not what we’re here to talk about! What we are here to talk about is more danmei! I’ve talked already about the validity of Asian queer content even if it’s not as wholesome by western values and I’ve also talked about queer-coding in Chinese media that features LGBTQ+ ships (whether they’re the main focus or not).

This time, we are going to talk solely about just danmei, where it’s supposed to be LGBTQ+-centric!

Of course, there are countless danmei novels out there now, and I can’t claim to be an expert on all of them. There’s some really passionate fans out there who’ve read hundreds of these novels, but I’ve actually only had the time to read a few… I hope to read more in the future, but a lot happens in life and it can be hard finding good translations sometimes! Plus, you guys know me… My speciality lies in donghua more so than danmei, as much as I love both.

So uh. I guess now’s as perfect a time as any to discuss some danmei donghua, and then if we have time, I’ll include some other danmei that I know are good!

We’ll start off with three classics: the animated adaptations of Mo Xiang Tong Xiu works (mostly because if I don’t include them, I’ll 100% be worthy of the label of a fake fan haha)!:

Mo Dao Zu Shi (The Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation):

I wouldn’t be surprised if you’ve heard of this one already. I’ve discussed this before, but this is one of three works by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu, and it was one of the first donghua to get popular outside of China. I have to commend its studio, BC May. They were a major player in building donghua’s reputation, considering both Mo Dao Zu Shi and Quan Zhi Gao Shou (The King’s Avatar) were donghua they worked on that happened to go viral in 2017-2018.

Mo Dao Zu Shi focuses on the titular grandmaster of demonic cultivation, Wei Wuxian, whose birth name is Wei Ying, after he is called back to the world of the living by Mo Xuanyu, who wishes him to get revenge on the family that has mistreated him his whole life… So yes, one of the first lines of this novel—which is also one of the first lines of the donghua—is that Wei Wuxian has died, a fact that amusingly shocks a number of newcomers to the series ahaha. But after he is revived, Wei Wuxian is confronted by numerous factors of his past, including the righteous Lan Wangji—birth name Lan Zhan—whom Wei Wuxian never really seemed to get along with too well.

As a demonic cultivator, Wei Wuxian immediately captures the attention of other cultivators, as many people remain in fear of his return from the grave, despite the fact he would’ve happily stayed dead if he could. This leads to him and Lan Wangji uncovering various secrets of their past, creating havoc in the cultivation world. It’s a story of intrigue, violence, forgiveness, change, war, and more—and it’s not one I’ll be reviewing in depth. Not right now, anyway. Mo Dao Zu Shi is a complex, multi-faceted story, and it’s far too intricate for me to tackle in what is essentially a listicle.

The one thing about its donghua adaptation is that it is gorgeous. The animation continuously improves throughout its three seasons, and the action is incredibly fluid. You may also notice a specialty of BC May’s, which is 3D backgrounds—or backgrounds with 3D elements—with 2D characters, and for the most part, they blend pretty well here, and the results are quite pretty. While I will say there is a bit of an issue with same-face syndrome (an issue that can occasionally plague anime art styles and is actually a weakness of the studio BC May in almost all their works), the character designs really are quite gorgeous—and now with so many different adaptations of Mo Dao Zu Shi, also iconic. With the donghua’s influence, Mo Dao Zu Shi has quite consistent designs that the fandom can draw on (hehe, pun not entirely intended) for fan art.

Many people have complained that Mo Dao Zu Shi is one of the subtler queer-coded donghua out there, especially considering the bigger audacity of Tian Guan Ci Fu, but I’ve always found it to nevertheless do a good job of depicting the main ship’s growing feelings for one another. Plus, season one more so covered Wei Wuxian’s past life and his growth into the Yiling Patriarch, so it makes sense that the romance was a lot more subdued at first. BC May did really up the ante in season 3 though, and fans have noted just how much more romantic it got, what with the adaptations of iconic scenes (no spoilers though!) like drunk Lan Wangji.

Because season 3 was its last season, the show did have to rush to adapt the rest of Mo Dao Zu Shi’s story, including the Yi City arc, one of its angstier stories. The rushedness does indeed show in the last few episodes as we hurtle towards the climax, but despite that weakness, BC May did a good job adapting it overall. For those who’ve watched the donghua already and would like to know my thoughts on the Yi City arc, you can read them in this Twitter thread here (a thread I may one day turn into a blog entry too haha, mostly because I really do find Xue Yang to be such a fascinating character).

The donghua did turn the novel’s timeline into something more linear, but I view it to this day as a pretty strong adaptation. Plus I’ll always have a soft spot for it, as it’s one of the first donghua that ever got me into this crazy world of donghua and danmei. The series even got a bonus chibi series in the form of Mo Dao Zu Shi Q (because “q” essentially captures the term “chibi” and “cute” in Chinese), which both had more visibly romantic undertones and some cute comedy and fluffy moments with all the characters getting along, serving as a balm to the knives of the main series—though beware, there are still a few knives hidden in there!

Of course, if you ever want a more accurate—and thus explicit—adaptation of Mo Dao Zu Shi, I must recommend the audio drama, which you can find on MaoEr FM. The manhua is also quite good, as it has less censorship than the donghua, but some censorship is there. That being said, you can totally find a few uncensored pages on Twitter~ *wink wink* If you’d like a different visual adaptation that’s still solid in quality—and arguably a more expansive, less fast-paced experience than the donghua—then you can try the live-action drama version, under the name Chen Qing Ling (The Untamed). This version does change things even more, but it has its merits and its fans!

In fact, it’s actually the third anniversary of The Untamed—it released on June 27—so it is truly a good time for me to be talking about this series! So happy third anniversary, The Untamed! 😆

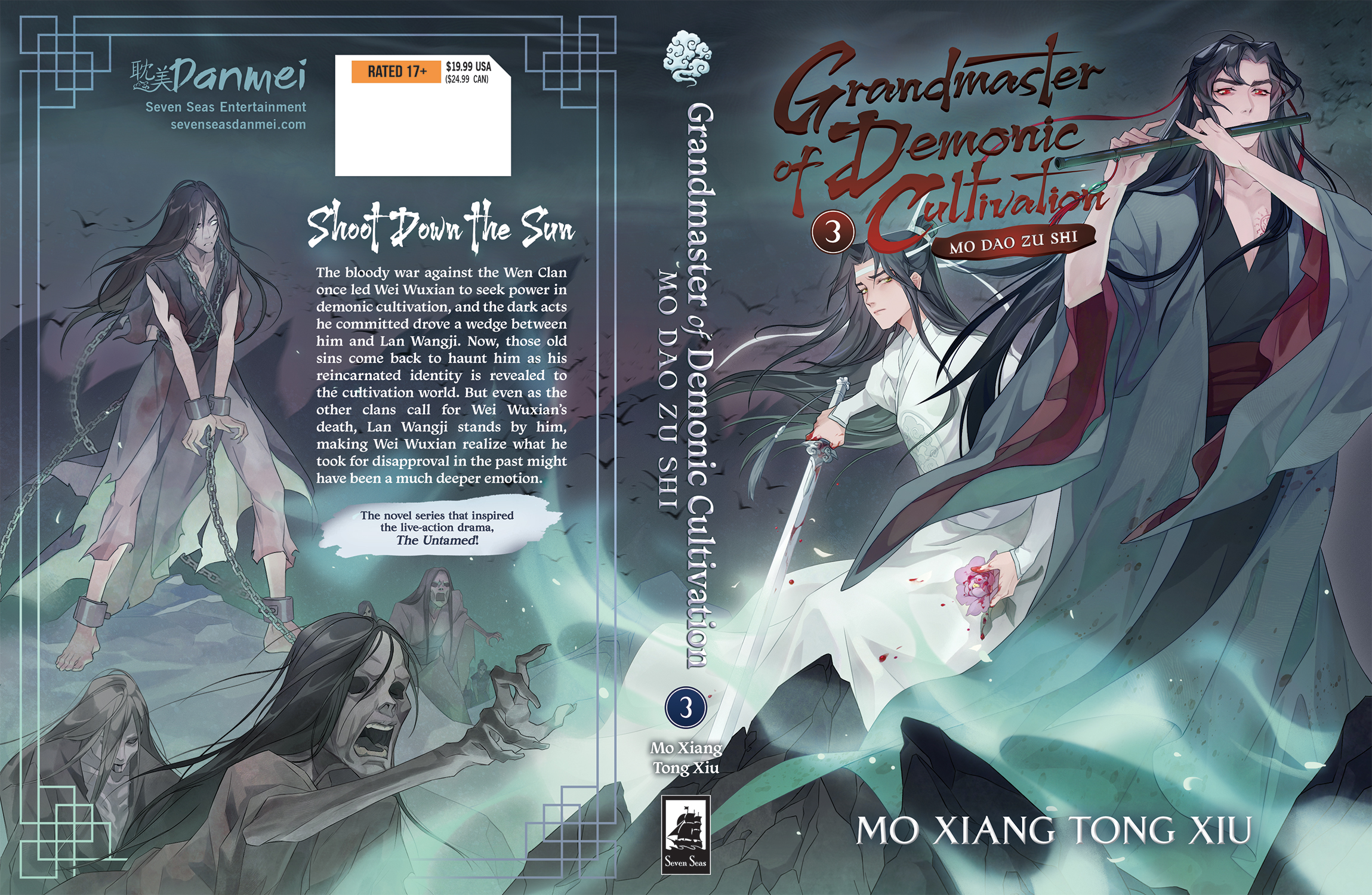

Oh, and the cover of the English translation of Mo Dao Zu Shi volume 3 was just recently released, so that’s good too (even more good because Seven Seas finally recognized the union its workers have formed!).

Tian Guan Ci Fu (Heaven’s Official Blessing):

Wow okay the last one got way too long, so this one should be a lot shorter, because I want to talk about more than just these three tonight. This shouldn’t be too hard of a feat though, as admittedly… I have yet to read Tian Guan Ci Fu. 😅

I know, I know! It makes me seem like such a fake Mo Xiang Tong Xiu fan, but forgive me… I have been too busy being plagued by other brain rots to currently pick up the behemoth that is Tian Guan Ci Fu, but I swear I will one day! Plus I can promise you there’s way more fans out there than you may expect that have yet to read all three of Mo Xiang Tong Xiu’s works, and as someone who has 2/3 read, at least I’m not too far behind! I can tell you that I know it’s another story full of complex themes, with war, intrigue, questions against authority, themes of redemption, true love, and more, and that many, many people love this novel.

The donghua itself is gorgeous. It has such fluid animation, with a perhaps softer look than that of Mo Dao Zu Shi. It opens with Xie Lian ascending to the heavens…for the third time. While eight hundred years ago, he was a powerful and beloved god, he is now a humble, scrap-collecting god trying to maintain his temple. But this changes when he seems to catch the interest of the Crimson Rain-Sought Flower Hua Cheng, a feared Ghost King. Soon after, he meets a youth named San Lang, and the duo end up on an adventure that will reveal mysteries of their past.

So yeah, it definitely sounds interesting, right? And I can promise you it is! Unlike Mo Dao Zu Shi, Tian Guan Ci Fu has only finished its first season so far, so it’s a good time to hop into the fandom to check it out! As I mentioned while discussing Mo Dao Zu Shi, Tian Guan Ci Fu gets a lot more daring with how it depicts its main couple: they share numerous cute moments that include some touchy-feely things in both the literal (skin-on-skin contact! *gasp*) and the metaphorical (touching our emotions! *double gasp*) sense.

It’s a very pretty donghua, and I definitely recommend checking it out! Similarly, the manhua is even more gorgeous, drawn in insane detail by STARember. I mean, just look at it! Isn’t it crazy how pretty it is!?:

There’s also an upcoming live-action adaptation and I heard stirrings about an audio drama adaptation? So definitely plenty to look forward to if you are—or are interested in becoming—a Tian Guan Ci Fu fan!

Chuan Shu Zijiu Zhinan (Scumbag System) aka Ren Zha Fanpai Zijiu Xitong (Scum Villain’s Self-Saving System):

I’m…just realizing that this is the only adaptation that has a different name from its novel counterpart lmao. But yeah, last but not least, here’s Chuan Shu! Based on Mo Xiang Tong Xiu’s first novel, Chuan Shu is what is commonly called a transmigraton story in Chinese fandoms (or an isekai for Japanese fandoms)—where the main character, Shen Yuan, ends up transmigrating into a novel as the titular scum villain, Shen Qingqiu. It’s a bit of a satire, meaning it has plenty of comedy. For example, the novel Shen Yuan got transmigrated into is a stallion novel—a male power fantasy where the overpowered protagonist beats everyone and gets all the ladies. This novel is one that Shen Yuan followed faithfully despite hating on it, and when it ends, he is so enraged he dies (how he dies varies from telling to telling, but it usually involves food of some kind haha. In Chuan Shu, he seemingly chokes on a bao). Now he has to use his knowledge to survive and avoid the scum villain Shen Qingqiu’s fate of being turned into a human stick by Luo Binghe…but it’s not as simple as he hopes. There’s the System—a common trope in transmigration stories—that prevents him from acting OOC (out-of-character) and who gives him missions to better the storyline, including the dreaded, important scene of Shen Qingqiu being forced to betray Luo Binghe and throw him down into the horrible Endless Abyss, which lies between the Demon and Human Realms. So as Shen Qingqiu, Shen Yuan has to gain Luo Binghe’s favour through more subtle means, and well…considering this is a danmei featuring a gay relationship…you can probably tell that things don’t exactly go according to his plan haha.

If any of you have been on my Twitter for even ten seconds, you must know that I love Scum Villain so so much. I’ve ranted a lot about why I love Luo Binghe as a character and why I think Shen Qingqiu makes for such a subversion-of-expectations type of protagonist, but also why I enjoy their dynamic—where the aloof master is actually forever eternally screaming and cursing inside while the powerful and scary Demon Lord is willing to round pleading, weeping puppy dog eyes on his lover. It’s just such a fun ship, and as it’s been a while since I’ve rambled about my love for them, hopefully I’ll get to doing so again in a future blog entry!

For now though, let’s talk the donghua: this the only one out of the three Mo Xiang Tong Xiu novels that got animated using CGI, and I have to say…I’m not surprised. Really, it feels like one of those cosmic fate situations where it’s just like, “Ah, of course it was Scum Villain that got the 3D animation treatment. Of course.” That’s not to say that the CGI is awful! You can kind of tell it’s a bit cheaply made at times, but it has its strengths, and truthfully speaking, China actually enjoys their 3D animation quite a bit, unlike Japan, and for the most part, these series look pretty good! Unlike Japanese 3D animation, where fans complain about the quality, especially when it is both cheap and fails in its attempt to imitate a 2D anime art style, Chinese 3D animation goes for a more realistic look. Even then, various studios have their own styles, and I’d recommend numerous series—should probably actually write a blog entry about CGI donghua sometime haha. Getting back to Chuan Shu though, I have to say… The main characters really got the luxury treatment~

Shen Qingqiu is unfairly beautiful and Luo Binghe is too—although what I really love this donghua for is its design for little baby Luo Binghe, who I—and many fans—lovingly call Bunhe. He’s just…so, so, sooooo cute. Look at his puppy dog eyes!! I literally have a whole Twitter thread of just Bunhe screenshots oh my god. I even have a reputation among my friends of crying on voice call because I see Bunhe—that’s how you know I love him ahaha.

Overall, Chuan Shu is a pretty faithful adaptation! We Scum Villain fans love it, and even if you’re not a Scum Villain fan, I’d nonetheless argue it’s a series of solid quality that can be enjoyed. It’s also helped by the stellar voice actors—did you know that characters such as Sha Hualing and the System share voices with Genshin Impact characters!? Of course though, the strongest of them all are the main characters—Shen Dawei has such a good range as both young, innocent Luo Binghe and older, darker Demon Lord Luo Binghe, and Wu Lei as Shen Qingqiu… I mean, do I even need to say anything!? Wu Lei is just an amazing voice actor who emotes so well. He similarly has an amazing range as Shen Dawei, as you can see by his professional shizun voice and his internal screaming voice. But also because he voices Yan Wushi of Qian Qiu (another danmei I’ll talk about in a bit), and in that one he uses both a powerful, sultry, deep, flirtatious, cocky voice and a sweet, innocent, higher-pitched, youthful voice, so really, his range is insane. You can find more of their voice work in this Chuan Shu and MaoEr FM collaboration, which I translated here. This collaboration includes numerous scenes and some interviews, and I have to say…they show that romance even more hehe (because remember, audio dramas are a lot less censored!).

But okay, this is starting to get long again, so I’ll try to wrap it up real quick: I’ve already mentioned how funny it is that of course Scum Villain got the 3D animation treatment, and that’s mostly because Scum Villain fans are some of the most starved fans out there. We had a manhua, but it got shut down due to controversy surrounding one of the manhua studio’s workers (who wasn’t even working on the Scum Villain manhua, by the way!). Then our donghua is plagued with a few financial issues, and besides a singular trailer and some holiday celebratory art/posts early on after the first season ended, it has been very, very quiet. It doesn’t help that before the first season, it was similarly quiet, with only the spinning character models to keep fans company, so fans joked Shen Qingqiu and Luo Binghe were “stuck in the microwave.”

In fact, there’s actually a funny story surrounding the models too. In the first trailer, the characters were less beautiful and more traditionally masculine, and fans complained so much that the studio redesigned them, which is how we got regally beautiful Shen Qingqiu and pretty boy Luo Binghe today. I like to joke that they probably realized they needed to hire a female character designer to better capture what the mostly female fanbase was expecting ahaha.

Continuing on about Scum Villain’s bad luck, unlike Mo Dao Zu Shi and Tian Guan Ci Fu, not only do we not have a manhua, we also don’t have any live-action drama adaptations like they do. In fact, Scum Villain sort of has a…rip-off (?) live-action version, as in there’s a cheaply-made web-drama series with a very similar premise to Scum Villain—even down to the fact one of the characters has a red mark on his forehead and he’s going after his master. Scum Villain fans also don’t have an audio drama—the closest thing is the Chuan Shu and MaoEr FM collaboration, but we did have a fan audio drama…that from what I know, seems to have been taken down. And that’s why Scum Villain fans are starving the most out of all of the Mo Xiang Tong Xiu fandoms. 😔

Conclusion:

Okay, wow, this got way too long for a singular blog entry, and it’s already past Sunday as a result. If I were to continue discussing danmei donghua the way I originally intended to, this entry would be way too long, and it would also be unfair because the other series would get shorter snippets than I’ve written for the Mo Xiang Tong Xiu donghua here. Considering I’m really tired, I guess I’ll stop here for tonight and just label this as Part 1!

In Part 2, I’ll touch on other animated series, some of which are also pretty popular, even if not to Mo Xiang Tong Xiu’s extent (such as Qian Qiu, Tianbao Fuyao Lu…) and some more underrated ones (such as Jie Yao, Wo Kai Dongwuyuan Naxie Nian…). For now though, I leave you with this Google Slides my friend Joel made about danmei, which includes info on various novels. I might try to touch more on danmei novels some day, but for now this will have to do.

PS: I’m not sure when I’ll be able to update my blog again, since I’ll be away for my convocation soon, and we might go on another road trip as a result, the way we did for my brother’s convocation. It’ll have to be seen, depending on whether I bring my laptop with me or not!

PPS: I’m excited because I’ll finally be watching Everything Everywhere All at Once very soon! As a Canadian-born-Chinese, I’m ready for that film to just absolutely fuck me up—pardon my language haha—and hopefully I’ll get to write a blog entry on it soon (speaking of, I should also write one on Turning Red…), so definitely lots of future blog entries I hope to write, which I suppose is a good thing! 🙈💕

Anyway, before June ends, I’m wishing you all happy Pride one last time~ 🌈